Chickens are thought to have been domesticated from the Red junglefowl thousands of years ago. First used for cock fighting, they eventually became prized for their eggs and meat. Over the course of many generations, different breeds of chickens emerged and were kept for specific valuable traits. A breed is considered a type of chicken for which offspring are identical to their parents—they must breed true.

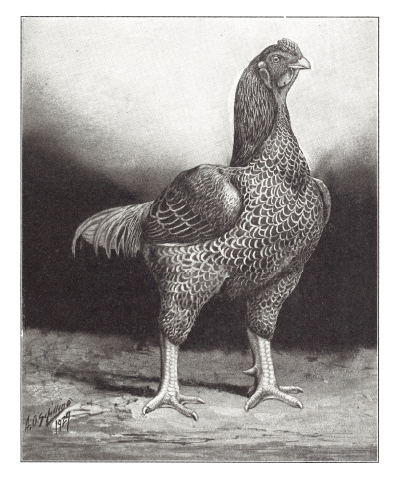

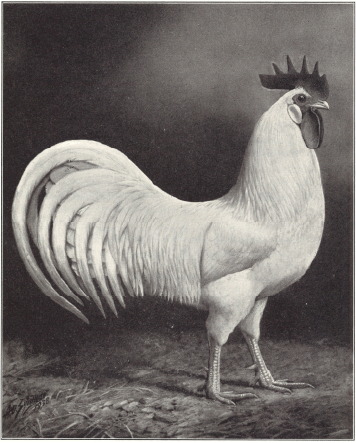

Throughout history, many breeds became known for the locations where they had developed. Leghorns are a smaller-bodied, white egg–laying breed known for their tense disposition, prolific egg-laying, and origination from the port of Leghorn in Italy. The Cornish are known as a stocky, slow-growing bird originating from Cornwall, England. These breeds were healthy and vibrant, well suited to living a long life outdoors in their local environment.

Cornish

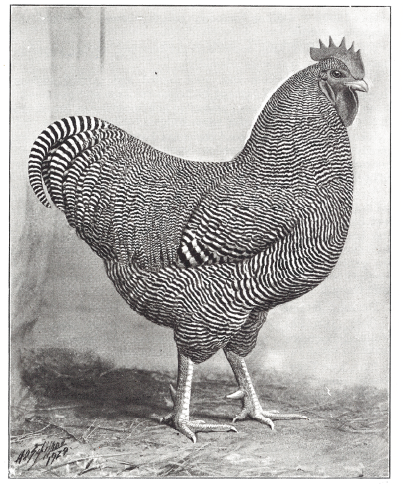

Plymouth Rock

Leghorn

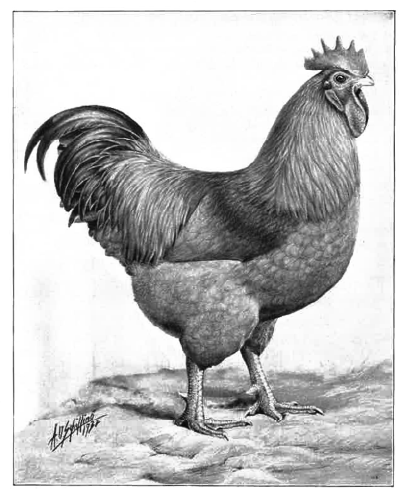

New Hampshire

When Western explorers discovered America, they brought breeds of chickens from all over the world to America’s shores. Americans mixed the imported chicken varieties to develop some of the best meat-inclined breeds ever produced. Notable among these were the Plymouth Rock, king of the broilers for decades, and the New Hampshire, a fast-growing, red-feathered bird that would go on to shortly take over the spotlight before the rise of industrial hybrids.

While new breeds such as these were developed from time to time, for thousands of years, most poultry keepers just kept whatever hatched on their farms. These mixed backyard birds, known as common fowl, were predominant in the mostly “small home flock” poultry industry of the past.

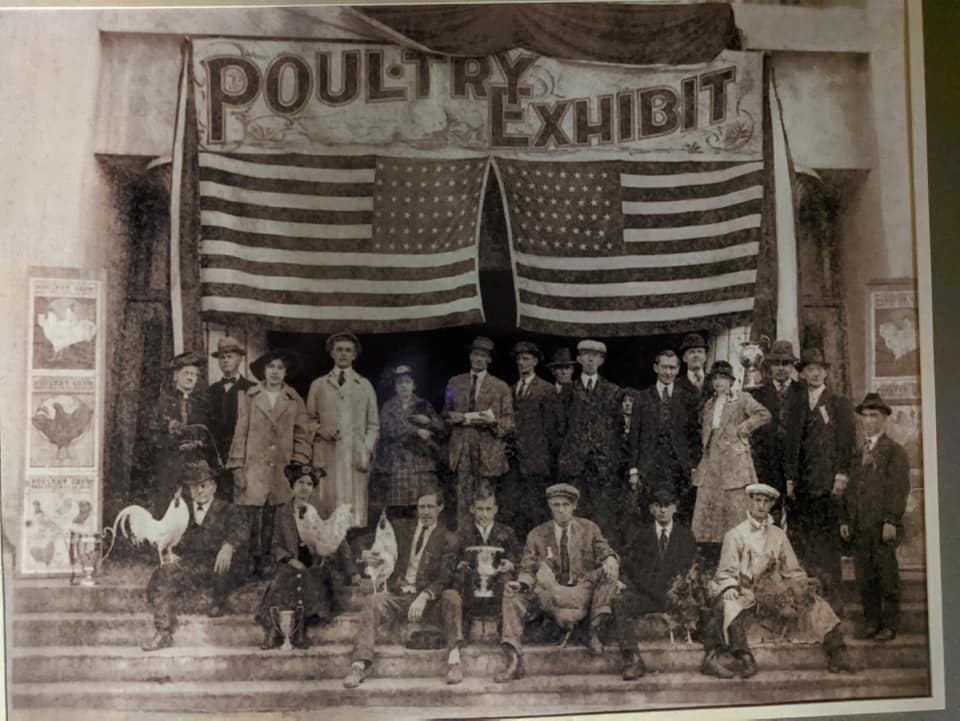

In the 1800s, a preference for purebred fowl began to take hold in the United States and elsewhere. By the mid-1800s, great confusion and widespread fraud necessitated that an overseeing body set official standards for poultry breeding. In 1873, the American Poultry Association was formed, and one year later, they codified the American Standards of Perfection to regulate poultry breeding standards.

The Standards of Perfection codified the specific details for each breed of poultry and ensured that they would be reliably reproduced from generation to generation. The first breed to be inducted into the standards was the Plymouth Rock, which became the most popular meat chicken in the United States for decades on end.

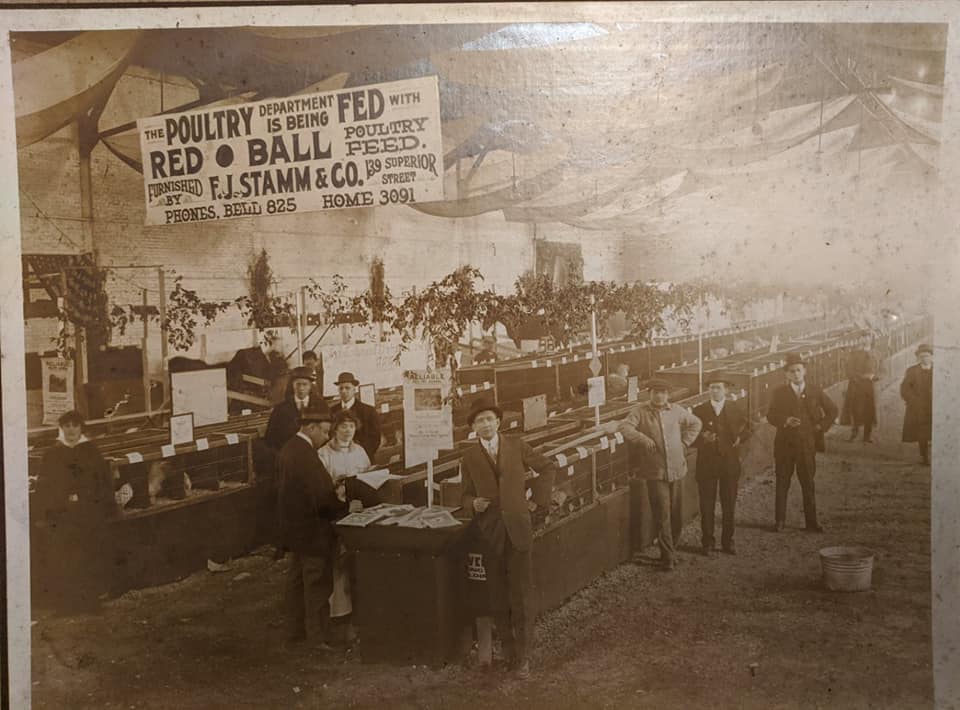

With this, quality bloodlines became highly praised in the United States, and the Standardbred poultry industry grew and took over the American poultry scene. Despite this growth, the industry was small in comparison to today’s poultry behemoths. At that time, poultry was a gourmet food, mostly reserved for the festive Sunday lunch and other special occasions. The industry was small and localized—growers mostly consisted of backyard farms, who would raise a few dozen birds for their eggs and meat. Modest breeders and butcher shops that supported these small producers littered the country.

USA’s first large broiler farm

Source – NPR & USDA

Modern broiler breeder farm

This couldn’t be more different from today’s poultry industry, where two large breeders (Cobb and Aviagen) control nearly all broiler genetics in the entire world. Whereas less than 15lbs of chicken was consumed annually per capita 100 years ago, today, chicken has overtaken pork and beef as the most popular meat in the United States, with a per-capita consumption of almost 100lbs2. Chicken is now the cheapest and plainest meat around, with about a quarter of what’s produced being used for fast food3.

So, what happened? How did this industry change so rapidly, and how did hybrids so thoroughly wipe out the old industry? These are questions we’ll be exploring in this series. We will look at important events in history that led to the rise of factory farm poultry, and we will envision a path forward toward restoring the Standardbred poultry industry. In part 2 of this series we will explore a fateful accident which was one of the greatest catalysts for the rise of industrial chicken and the factory farm model.